put on the fire in an earthenware pan with cool water and 3 grams of baking soda tied in a piece of cheesecloth. This is what people call “the secret trick”, and it makes cooking chickpeas easier.

CHICKPEA FRITTERS

INGREDIENTS (SERVES 4-6 PEOPLE)

- Dried Organic Chickpeas 300 g

- 7 or 8 dried chestnuts

- 3 g baking soda

- salt to taste

- Sapa (cooked must) to taste (3-4 tablespoons) or 80 g of sugar

- half a jar of Savignano mostarda (100 g drained weight) or 7 g of powdered mustard dissolved in the hot chickpea water

- 40 g candied fruit in small pieces

- sugar to taste

- 2 teaspoons cinnamon powder

INGREDIENTS FOR THE DOUGH

- 270 g flour

- 20 g butter

- 15 g sugar

- 1 egg

- 3 tablespoons white wine or Marsala

- salt to taste

DIRECTIONS

Original recipe by Pellegrino Artusi.

Take 300 grams of dried chickpeas (I specify dried, because in Tuscany they’re sold softened in the water from salt cod).

Soak the chickpeas overnight in cool water, and the next morning add 7 or 8 dried chestnuts; put on the fire in an earthenware pan with cool water and 3 grams of baking soda tied in a piece of cheesecloth. This is what people call “the secret trick”, and it makes cooking chickpeas easier. Instead of baking soda, you can also use lye water.

The evening before, put the chickpeas in any type of jar, and cover the mouth of the jar with a cloth on which you’ve placed a shovelful of ashes; pour boiling water through the cloth until the chickpeas are covered. The next morning, remove the chickpeas from the lye water and rinse thoroughly with cool water before you put them on the fire. When the chickpeas are cooked, remove them from the water and strain them through a sieve while they’re still piping hot, along with the chestnuts. If in spite of the “secret trick” with the baking soda or the lye water they’re still too hard, crush them in a mortar. After you’ve strained them, season with a pinch of salt, enough cooked must to soften the mixture, half a jar of Savignano mostarda (or the relish described in recipe 788), 40 grams of candied fruit in small pieces, a little sugar if the must hasn’t sweetened the chickpeas enough, and two teaspoons of ground cinnamon. If you don’t have a horse, you try to get your donkey to trot: and in this case, if you have neither cooked must nor mostarda (for my tastes, the best mostarda is the one from the town of Savignano in the Romagna region), you can substitute 80 grams of sugar for the former and 7 grams of powdered mustard dissolved in the hot water in which you cooked the chickpeas for the latter.

Now we’ll go on to the dough in which you’ll put the filling. You can half the recipe for Cenci, no. 595, or else use the following ingredients:

- 270 g flour

- 20 g butter

- 15 g sugar

- 1 egg

- about 3 tablespoons of white wine or Marsala

- a pinch of salt

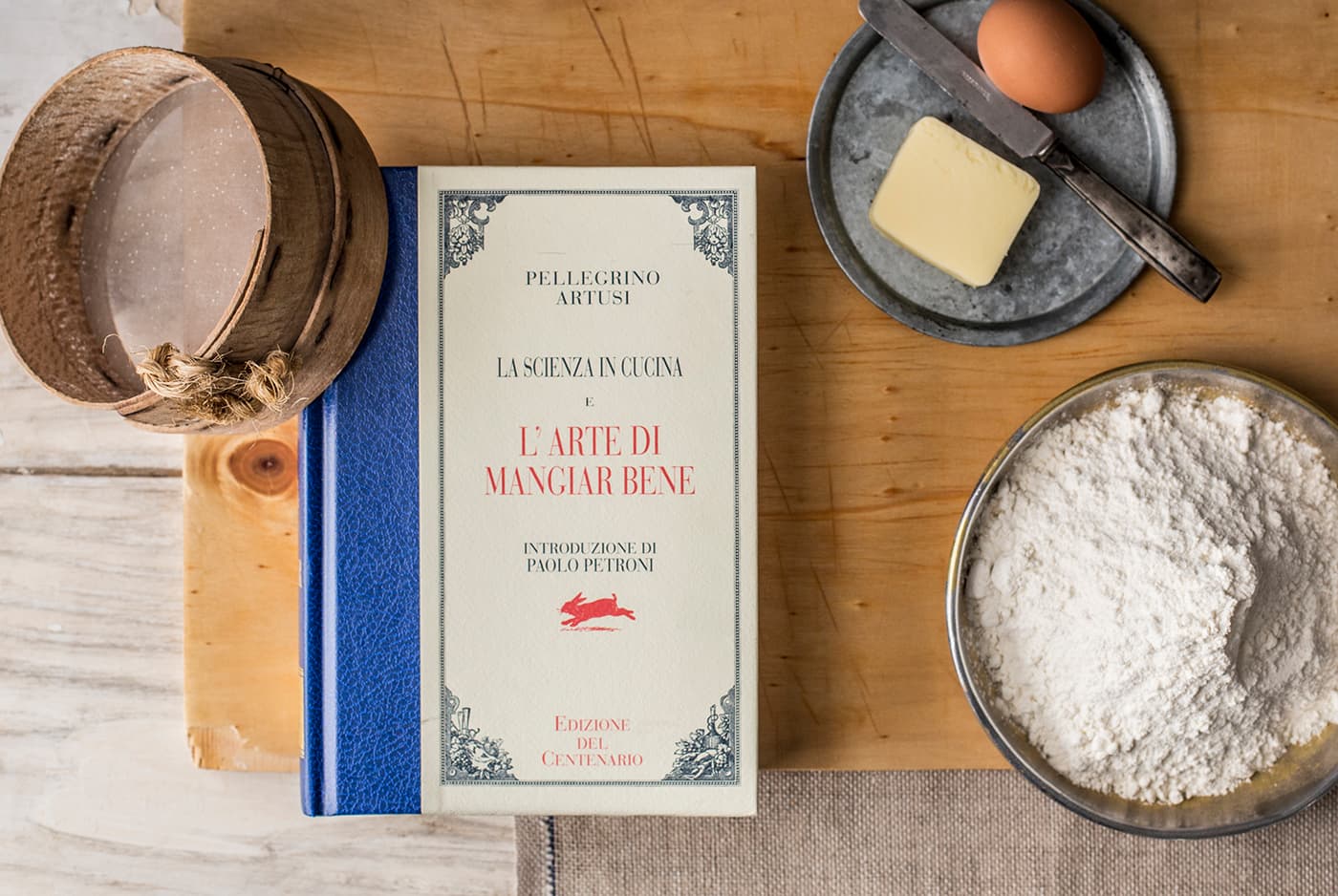

“Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well” is the well-known manual by Pellegrino Artusi, written in the late 1800s.

This book, which stems from his travels throughout Italy, contains more than 700 homemade recipes, but there are also personal notes, as well as pearls of wisdom and ironic phrases by the writer and gastronomist. Due to its historical and cultural value, this masterpiece of Italian cuisine and table service has been translated into numerous languages and is known throughout the world.

Pellegrino Artusi - a “peregrin” both by name and by nature - was born in Forlimpopoli in 1820 and died in Florence in 1911. He was an Italian writer, gastronomist and literary critic. His most notable work is the well-known cookbook “Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well”.